What Is an Aebersold Play-A-Long?

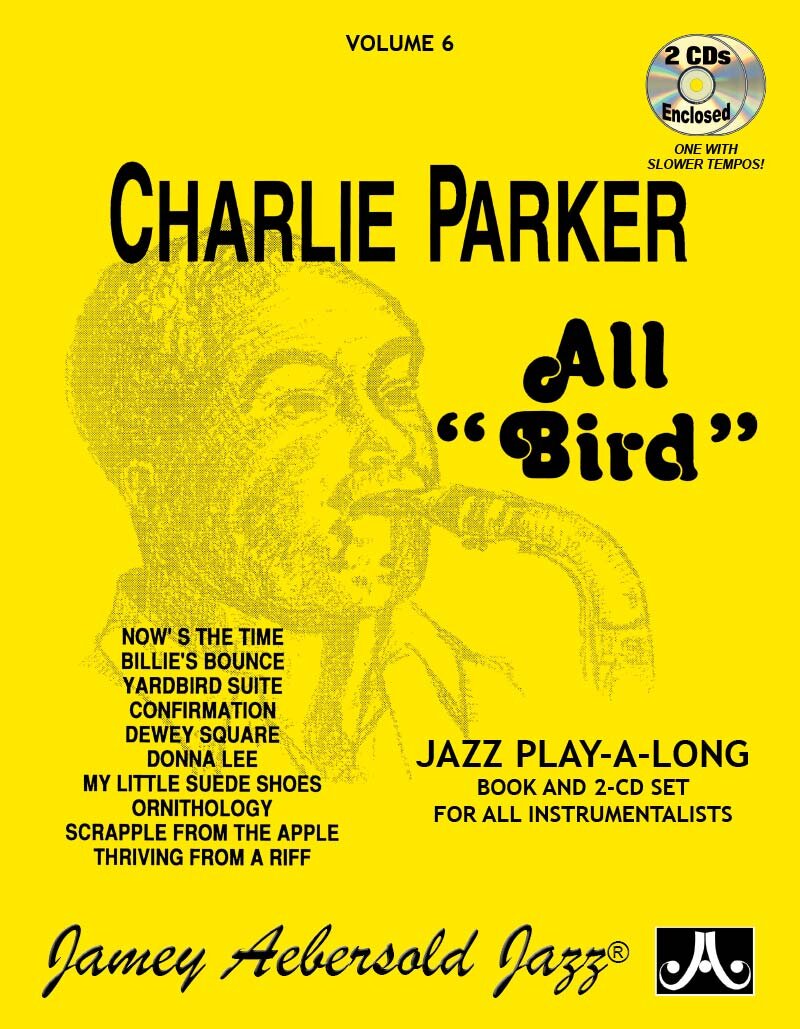

It is a stereo recording of a jazz rhythm trio--piano (or guitar), bass and drums. The series began as vinyl LP albums in 1967, and evolved to cassettes, compact discs, and a streaming service. A printed book comes with the recording. The book generally contains jazz chord symbols (“changes”) and often the melody (tune) to a dozen or more commonly played jazz and popular standards. Melody and chord symbols are all presented in treble and bass clef, B-flat transposition, and E-flat transposition, suitable for all jazz instrumentalists.

The player plays along with the excellent rhythm section, and should quickly learn the entire tune and correct chords. The player also gains the experience of playing with a fine accompaniment, and is encouraged to improvise new material in appropriate jazz styles and tempos.

Aebersold used the left/right channel separation, enabling players to listen to the entire rhythm trio, or only piano and drums, or only bass and drums. Most windplayers would usually choose the very good full trio, but pianists and bassists could also practice with or without the recorded artist.

Tunes generally are presented in “standard instrumental keys” so when you learn them, you are ready for a jam session. The vocal Play-A-Long tracks are presented in singer keys and some have high and low voice tracks. Volumes like number 3,21,24, and 84 present musical licks, patterns, and phrases that help one learn the “jazz language.” The keys may not have been standardized years ago, but students have quickly learned the songs in these keys, and may rarely play them in any other keys, despite continual encouragement to eventually learn to transpose, and know and play the songs in almost any key.

Several of the albums are not focused on standard tunes, but instead teach “chord-scales” and other jazz theory, various common chord progressions, and sometimes some recommended musical phrases to get started.

The Aebersold Play-A-Longs have become immensely popular among jazz students, teachers and professional musicians worldwide. All told, Aebersold issued 133 Play-A-Long albums. Many have been revised or expanded one or more times, and some albums now contain two CDs, one with slower tempos. The albums also are available via a streaming service.

“There will always be Play-A-Longs and, thanks to Jamey’s vision, jazz education has never been more effective.”

Jazz Education Before Play-A-Longs

First, there was the published sheet music, usually piano arrangements. To learn songs and absorb styles, musicians listened to recordings repeatedly on phonographs or on radio. Many students formed their own bands and generally played published “stock” arrangements.

Playing by ear usually was frowned upon in formal music lessons. Some traditional teachers considered it cheating to play by ear (memorization was acceptable), and they felt that jazz styles (Swing, Dixie, Blues, Country, Gospel, Pop, Rock) were inferior, dirty or dangerous, and too easy. A few schools had dance bands or pep bands, but rarely for credit, and usually after school hours.

Jazz playing was only infrequently taught (often in military bands for performance). Aspiring players generally picked it up from the more experienced players on the bandstand (or they did not), and from recordings. Many students learned by playing with these recordings. There were relatively few published books, emphasizing “licks” and transcribed solos. “Jazz theory” was slowly evolving, far behind classical harmonic styles.

Players often made their own handwritten “lead sheets” containing only the basics: melody, their own favorite symbols for chords, and maybe the lyrics. They could compose/improvise their own voicings and embellishments from this lead sheet, and “fake it.” There were Tune-Dex cards (miniature lead sheets on index cards), “fake books” (two and three songs per page in lead sheet format), and then The Real Book(s) which contained far fewer old songs and more of the younger jazz tunes (including Bebop and modal jazz ) which were becoming standards for jazz players.

In the 1950s came “Music Minus One” LP vinyl recordings, and other brands, including a surprising amount of jazz material. Photocopiers became affordable during the 1960s, enabling easy and inexpensive copying and sharing of lead sheets, band arrangements and books.

“Jazz camps” and workshops grew in popularity during the 1960s, most often during summer vacations. Publication of jazz ensemble arrangements (charts) rapidly proliferated. Slowly a few more colleges added credit for jazz ensembles. The notation of chord symbols gradually became more standardized.

The faculty at these camps and workshops, professional musicians and effective educators, became an informal cadre who shared their instructional ideas and techniques with each other and with many thousands of students.

Jazz education was quickly gaining respect as evidenced by the establishment of the National Association of Jazz Educators (NAJE) in 1968, followed by the International Association of Jazz Educators (IAJE) in 1971 and the Jazz Education Network (JEN), which still exists today.

This confluence of events culminates with the publication and release of the first Aebersold Play-A-Long, “A New Approach to Jazz Improvisation,” in 1967. Aebersold has told interviewers that he viewed this as a “one-off,” or a “one and done,” project. That would not be the case.

“Listening is the key to everything good in music.”

Play-A-Long Tips for Players and Teachers

Artists, educators, and students suggested how to make playing along with the Aebersold Play-A-Longs even more varied, fun, and beneficial.

Perhaps the most common use is to choose a volume, pick a tune, and play along.

But we do get tired in the embouchure or the hands, or we feel we are playing too much of the same stuff. When this happens to you, take breaks: sing a chorus, or two. Or really listen to that rhythm section with focus.

Memorize the tune and the correct chords. Learn the facts, do the work, don’t be a faker. Sometimes, analyze the tune and chords and form.

It really is fun to “pan out” the left or right track, even for wind players, and play for a while with bass only, or piano only.

If your hardware and software permit, do challenge yourself with other keys and other tempos. Or you might make a loop that repeats a problem bridge (for instance) over and over until you’ve solved it.

Or practice playing with a buddy, another player or singer. You can trade choruses, or 16 measures, or 8s or 4s. Expect to absorb quite a lot and to get many musical ideas from each other. No pressure! Your buddy can certainly play a different instrument and can be more advanced than you (teacher/student), or less advanced. Expect that you may crash at times, then laugh and continue.

Some less experienced players would benefit from just playing with the rhythm section instead of live players.

You can, of course, play one certain track repeatedly, to get it right. Or just run through several sides, an entire album or more. Both have value.

Here are some additional ideas to broaden jazz vocabulary and musical imagination.

- Shorter phrases, or longer phrases.

- More chromatic passing tones. More pickups.

- Fewer scales and more wider intervals.

- More spaces, more silence.

- A wider variety of note lengths.

- Pace, and change of pace. More triplets, for instance.

- More, or less, blues flavor.

- Mostly ascending phrases.

- Mostly descending phrases.

- Focusing on some technical issue (speed, range, embouchure, vibrato, fingerings, voicings, right or left hand).

- Dynamics: can I play just as well softly, or very powerfully?

- Some bits of alternative chords, some reharmonizing, or “half-changes.”

- Embellishments: rubato (fall behind), scoops, glisses (scale or chromatic fills), falls, flips and turns, mutes, pedals.

- Eyes closed or eyes wide open and looking around. Looking at someone.

- Moving my body more, or less.